The unprecedented death and destruction wrought by World War I leveled economies the world over, but the situation was different in the United States.

The unprecedented death and destruction wrought by World War I leveled economies the world over, but the situation was different in the United States.

In fact, 1914 to 1918 were mostly boom years for the U.S. as the federal government poured money into the wartime economy. Previously a debtor nation, the U.S. emerged from the war as a chief lender and arguably the strongest and most vibrant economy in the world.

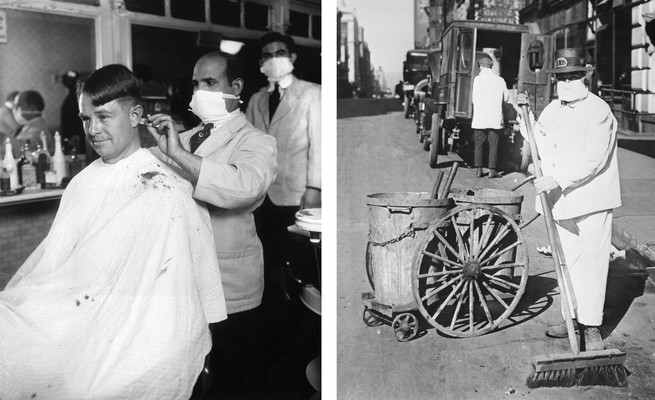

But even that wartime boom doesn’t fully explain what happened next. Somehow, despite a global flu pandemic that killed 675,000 Americans in 1918 and 1919, and a depression that gutted the economy in 1920 and 1921, the United States not only recovered but entered into a decade of unprecedented growth and prosperity. Americans began a spending spree: the Roaring Twenties was on.

The Spanish Flu Was Deadlier Than WWI

The ‘Boomlet’ Before the Bust

The Federal Reserve, created in 1913, flexed its monetary policy muscles for the first time during World War I. Since the American public was unwilling to fund the war effort through taxes, the Fed did it by printing more money. The result by 1918 was runaway inflation. A pair of shoes that cost $3 before the war now cost $10 or $12.

Economists predicted a post-war crash as military factory orders dried up after the 1918 Armistice. Compounding the end of the wartime economy was the spread of the so-called “Spanish flu,” a virulent contagion which not only killed hundreds of thousands of Americans from the fall of 1918 to the spring of 1919, but shuttered businesses from coast to coast.

Incredibly, the dire post-war economic predictions didn’t come true. At least not immediately. American consumers, who had patriotically scrimped and saved during wartime, began to live it up. Europeans also joined in, purchasing $8 billion in exports from America. Inflation ticked upward, and so did prices, but consumers were willing to pay anything for a taste of freedom.

“Instead of the deflationary slump widely expected, the economy experienced an inflationary boomlet, and everybody exhaled,” says James Grant, the author of The Forgotten Depression: 1921: The Crash that Cured Itself. “The inevitable did happen, but it didn’t happen on schedule.”

Not ‘Great,’ But Still a Depression

To combat skyrocketing inflation, the Fed kept raising its discount interest rate to make borrowing more expensive. By 1920, the interest rate had reached 7 percent, what Grant calls “horrifically high.”

While the Fed had the right idea, the timing was not good. The surprise post-war inflationary bubble was about to burst. Sector by sector, market by market, prices began to plummet as the once-exuberant consumer demand dried up. And with interest rates sky high, businesses couldn’t afford to borrow money to stay afloat.

Grant argues that the Fed absolutely could have intervened by slashing interest rates, and Congress could have passed fat stimulus packages to prop up failing industries, but instead, U.S. leaders chose the path of laissez-faire.

Benjamin Strong, the influential governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York at the time, was clear-eyed in his prediction of what inaction would do to the economy.

“I believe that this period will be accompanied by a considerable degree of unemployment, but not for very long,” he wrote in February of 1919. “And that after a year or two of discomfort, embarrassment, some losses, some disorders caused by unemployment, we will emerge with an almost invincible banking position… and be able to exercise a wide and important influence in restoring the world to a normal and livable condition.”

And that’s precisely what happened. The depression of 1920 and 1921 lasted 18 months, what Grant calls a “brutally hard, but very efficient depression.” The stock market lost nearly half its value, unemployment reached 19 percent, and countless businesses went bankrupt, including Truman & Jacobson, a men’s clothing store in Kansas City co-owned by future U.S. president Harry Truman.

A Nation ‘On Sale’

The bitter economic pill prescribed by Strong worked as intended, and prices came down. And in 1921, the newly appointed Secretary of the Treasury, wealthy industrialist Andrew Mellon, pressed the Fed to finally lower interest rates.

With deflated prices for goods and lower borrowing costs, “The country was on sale,” says Grant. Foreign investors flooded the economy with gold and that provided the capital to get the ball rolling again domestically.

“Free markets were their own beacon,” says Grant. “Gold rushed into the country to profit by the coming boom, and sure enough there was a boom, and the 1920s really ‘roared.’”

Back to ‘Normal’ in a Big Way

The Roaring Twenties deserves its name—the U.S. economy grew by 42 percent from 1921 to 1929. But economic historians argue that the factors that made the decade so profitable were less of an anomaly than a return to normalcy.

Even the biggest technological advances of the 1920s—widespread electrification of homes and factories, the introduction of household appliances like refrigerators and washing machines, rapid adoption of the automobile, the growth of commercial radio stations and cinemas—were in development before World War I hit the “pause” button.

“The war may have accelerated development of aircraft, but in general, in the 1920s you got back to normal economic growth and normal economic business cycle,” says Hugh Rockoff, a professor of economic history at Rutgers University.

The Roar of the Roaring Twenties Is Silenced

Much of the skyrocketing wealth of the 1920s was built on a shaky foundation of easy credit and stock market speculation. The same laissez-faire governing philosophy that righted the economic ship in 1921 failed to avert the 1929 stock market crash and prevent unregulated American banks from going belly up.

After a great exhale following war and pandemic, Americans now faced the Great Depression.